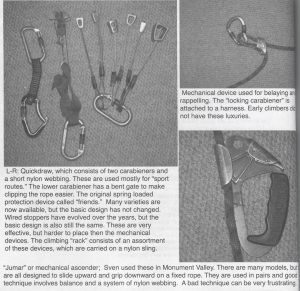

Most technical climbing routes are climbed with a team of two. The climbers wear specially designed harnesses which are attached to opposite ends of the climbing rope and climb one at a time. The lead climber moves boldly up the rock face and sets up a protection system by placing chocks or cams (See photo) into the cracks in the rock. The rope is then attached to the protection with a system of caribiners and nylon webbing, so that the leader will be protected if he or she falls. The second member of the team feeds the rope very carefully with a braking device that will stop the rope if the leader falls or needs to rest.

Technical climbs are divided into pitches that average about 100 feet. The leader will climb to a convenient ledge and set up an anchoring system. He or she will then yell “off belay” to the second climber and prepare to belay them up to the ledge. The second climber is still climbing the same rock, but the tight rope assures them of a relatively safe voyage. Going first is a much greater risk, because if the leader falls, he will fall at least twice the distance from his closest protection, and if one of the pieces fails to hold his weight, he could fall much further. For this reason, lead falls are highly discouraged. This method is now called traditional or trad climbing, and is the method used for the stories in this book.

Modern technology and changing attitudes have created a whole new sport called “sport climbing” which involves climbing routes that have fixed bolts for protection. This sport encourages climbers to try much harder routes and is relatively safe. I have spent most of my life trying to stay out of the ethical battles of climbing, but I do think that it is very polite for the young climbers to put up safe routes for us old guys. The new school of sport climbing provides anchors at very short distances and makes leading a lot safer.

THE CLIMBING SCALE

The diversity of our small planet has created at least ten different climbing scales. But the standard scale in North America, and the one that is referred to in this book, is the rock climbing portion of the Yosemite decimal system (YDS) which was developed by a California chapter of the Sierra club in the nineteen-fifties. The original scale for free climbs requiring ropes and technical skills ranged from 5.0 to 5.9, but the top of the scale was challenged almost instantly by the best climbers. Spider-man shoes and better athletes have pushed the modern scale up to 5.15, but the many transitions of the constantly changing scale have caused a discrepancy in many of the ratings. This is particularly true for the 5.9 rating, because it was the first to change. The name of a route and it’s difficulty is declared by the first climbers to ascend it successfully, but many of the early climbers were more skilled than they thought and they did not want to overrate a route, so an old 5.9 might be a 5.11. This is an added challenge that must be considered when choosing routes.

Most guidebooks also offer an R and X category to climbs that are difficult or impossible for the leader to protect. An R rating means that the protection is hard to place and that the leader could be faced with a very long fall. An X rating means that the lead is essentially a free solo and that falling is not an option.

Free climbing requires that the climber uses only the natural rock for hand and footholds. The rope is merely a safety net, and is not used for upward progress or resting. A successful climber will feel like he could have climbed the route without the rope. Free climbing is often confused with free soloing, but the sports are very different. Free soloing eliminates the rope, so the stakes are very high because a fall will mean death or very serious injury. There are a few very confident climbers who prefer this method because it eliminates the gear and provides an existential experience that might be the ultimate adrenaline rush. Because of the extreme consequences of a fall, the solo climber needs a cool head and very solid skills.

Direct aid climbing is a much different sport which uses climbing gear to gain altitude. Direct aid is often used to enable climbers to progress up a steep section of a route that they could not free climb. It involves challenging techniques and large quantities of gear, and has been used extensively on the big walls in Yosemite and many early first ascents.