“I would rather wake up in the middle of nowhere than in any city on earth. “

Steve McQueen

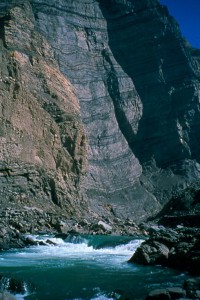

I wake up at dawn, and my senses are instantly overwhelmed by the incredible colors and the stark emptiness of the huge canyon where we have just spent the night. The experience feels almost like a dream, but I quickly remember where we are and recall the events of the last few days. It is the third day of our expedition, but we have only traveled about six miles, and have already lost two of the original six members of our group. Our camp is in the bottom of Peru’s infamous Colca Canyon which is a very steep and narrow gorge, with loose rock walls and difficult-to-impossible escape routes.

I suddenly recalled what my friend Dave Black had told me before the trip: “It’s a real scary canyon! The rapids are always changing, and there is one Class V rapid that is very hard to scout and cannot be portaged. Every run is essentially a first descent.”

Dave had lived in Peru for a couple of years and had run many difficult rivers, so I respected his opinion. But I also really wanted to do the Colca. Stories we’d heard of huge condors and incredible vistas had lured us there, and besides, the Polish team that had made the first descent in 1981 had survived in spite of their very primitive non-self-bailing rafts.

Our expedition had started at a rustic cafe called Sue’s Place in the small village of Huambo, which sits near the rim of the great canyon. Sue was a friendly host, and she let us stash our kayaks and gear in the back of her restaurant while we roamed the streets in search of a place to spend the night.

Most of the villages in South America have a main square, a Catholic church, and a soccer field. I had never seen one that didn’t.

When the Spaniards conquered the Incas, they melted many of their artifacts to forge bells for the new churches, and Huambo had an adobe church with two very large bells.

Our friends from Arequipa had given us a ride, and we had spent a very enjoyable day crossing the stark Atacama Desert. A few, very large volcanoes towered above the bare landscape and helped to create a moon like or almost prehistoric setting.

We were already a bit apprehensive about our expedition, and this scenic journey provided a detailed view of how remote this canyon really was.

The days are short on the equator, and the nights were cold in the high desert, so when the sun hit the horizon, we scurried back to a festive dinner that Sue had prepared. We would be limited to rations of PowerBars and dried food soon enough, so we ate heartily, and the Chilean wine flowed freely.

The arrieros (burro drivers) arrived the next morning, and after a serious discussion in Spanglish, we agreed on a price and started to load the caravan.

“Hey! That’s my boat!” Randy exclaimed, as one of the burros broke loose and bucked vigorously in the main square.

Our fearless arrieros managed to catch him, and the parade through the streets of Huambo began. This difficult burro shuttle involved about fifteen miles of a knee-jarring trail that hung on the edge of nearly vertical cliffs. At one point, we were forced to watch, helpless, as the burros nearly slid down a steep scree slope that had buried the trail. Our Peruvian friends had told us a few stories about lost burros and boats, and we were very happy to reach the bottom.

The first day on the river had been very mellow — only three miles of easy paddling and a great hike into a beautiful side canyon with emerald-clear water. The water was warm and deep, and we enjoyed a relaxed day in an empty paradise.

It felt great to get some rest, because we thought the next day would begin with an arduous portage that was supposed to be half a mile of steep and loose talus. This feature had been caused by a huge landslide that had dammed the river for two months, and had probably occurred during one of Peru’s many earthquakes.

We started early and stopped to scout the big slide. But, to our surprise, most of the debris had already been washed downstream by huge floods, and a few Class V rapids had been left to challenge us.

We paddled carefully and had managed to run most of the drops when we arrived at a short rapid with a big drop and a very nasty looking hole. There was a thin line on the right that didn’t look too bad, and Dave offered to be the probe.

He made it look a little too easy! I tried to follow his line, but the water was pushing harder to the left than I had thought it would, and my heavy boat caught the edge of the big hydraulic feature. The force of the falling water was pushing the back of my boat into the hole, and I nearly back-endoed, but I managed to keep my balance and escape the deadly current with a desperate brace stroke. The near catastrophe pushed my adrenaline to near-record levels, but I was able to catch a small eddy on river left, where I struggled to catch my breath. I tried to get Ken’s attention, but he had seen Dave’s clean run and was already getting into his boat.

In many rapids, a few inches or a slight difference in boat speed can be the difference between a clean run and a disaster. Ken’s line was a little farther left than mine had been, and the strong current grabbed his boat and back-endoed it right into the big hole. He put up a gallant effort, but the hydraulic forces would not release him.

“He’s swimming!” Dave yelled, and we rushed out to push him into an eddy before the next rapid.

“Thanks. I’m fine,” Ken said. “Where is my boat?” We searched diligently, but the boat had disappeared, and the sheer canyon walls made it impossible to get back upstream even if we found it downriver.

“I don’t see any other choice except hiking out,” Tom declared. “At least we are close to the trail that we hiked yesterday, and I think that you can get back to it from the top of that scree pile where we scouted.”

“I’ll go along,” Dr. Bill volunteered. “ I came for an adventure, and I think that hiking out will definitely be one.”

We all agreed that it would be better to have two people hiking out together. If they could get out, we reasoned, then someone could also hike in, which meant that Bill could leave his boat and attempt to retrieve it later.

Ken and Bill had to swim across a small channel, so we assisted them with safety ropes and then helped them haul their gear up the loose-rock slope.

“If I went alone, I wouldn’t have any stuff to carry,” Ken joked, as he helped carry some of the gear Bill decided to pack out.

He was trying to stay in good spirits, but it was obvious that he was quite bummed out about having to abandon the trip. When we parted ways, we could only watch in sympathy as they disappeared up the slope.

Our plan was to wait until eleven the next morning to make sure that they had been able to get out of the canyon. But if they came back, we were prepared to rush downstream to organize a rescue.

The remaining part of the group was up early after a restless night, but we waited as promised just in case our friends needed our help. At ten-thirty, we started to pack our boats, preparing to leave.

“It’s eleven o’clock, so they must have made it,” Tom said, heading toward his boat. “Let’s go find out what is waiting for us.”

There were now only four members in our group, and our feelings had become a lot more intense. We were all very anxious about the dangers we would encounter downstream as we headed deeper into the shear walled gorge.

The rapid below our camp was only Class III, and within a mile, we found Ken’s boat. A few small items were quickly salvaged and we left everything else on the rocks to dry. The day was waning, and the anxiety of the unknown pushed us onward.

The canyon became even more spectacular, with its ominous sheer walls and some very narrow passages. But the rapids were mostly Class III, and we moved onward with ease. Some very large condors circled above, hoping we would get munched in one of the rapids, and their presence made the canyon feel very eerie. It was almost as if we had passed through time and entered an ancient world in the very bowels of the Earth. There were no roads, no people, and not even an airplane to distract us from the serenity of this remarkable world.

“I think that’s Jasmine,” Randy shouted, as we approached a side canyon with a pleasant beach and a small, clear stream on river left.

We stopped to hike up a sensational gorge with bright red, brown, and gray walls that were enhanced by the tilts and swirls of the constantly changing geology. But after a few minutes, we had to rush back to our boats when rocks falling from the unstable walls nearly hit us.

This had been recommended as a camp, but there was too much exposure to falling rocks. So we found a sheltered spot for lunch and continued downstream to the Ducha del Cóndores (The Shower of the Condors) — a 3,000-foot waterfall in one of the most remarkable parts of the gorge.

It looked like a fairly safe camp, and the entertainment was fabulous, so we found a comfortable rock and enjoyed a great afternoon show.

These huge and mysterious birds, with wingspans of ten feet or more, roost in the Colca, but often travel some fifty miles to the Pacific Ocean, where they feed on whatever the sea gives them. When they come back to the canyon in the evening, they fly through the mist of the falls before returning to their nests. We saw at least half a dozen of the great birds as they flew through the falls, and one of them circled very close, then landed right across the river from us. We were trying to get a photo when we were suddenly distracted by a very loud noise.

“Crash! Bang! Bang! Boom! Splash!” A large rock landed in the river about thirty feet away.

“I’m moving my tent,” Dave said nervously. “I don’t like the looks of that wall. It is funneling everything that falls above us right toward our camp.”

I decided to join him, and we found a large overhang about a hundred yards upstream. The overhang was also filled with loose rocks, but at least those potential missiles couldn’t gain quite as much momentum, and we were sheltered from rocks falling from the upper canyon.

Randy and Tom were reluctant to move because they felt that the whole canyon was dangerous, and they were also fairly confident that their good karma would protect them.

We all survived the night’s rock falls and awoke early, ready for more action. But soon, we realized that two members of the group were struggling with some serious digestive problems. Randy and I had arrived early and already had one river and three weeks of adaptation behind us, but Dave and Tom had contracted a local stomach bug and were moving very slowly. Some hot tea helped revive them, and we managed a late start.

We cruised through an absolutely stunning canyon, with some very narrow passages. The forces of nature slowly create the best architecture in the world, and this was one of her finest projects. Chocolate Canyon was named for the amazing shades of brown rocks that swirl like an ice cream cone amidst the bright reds and yellows of the immense sheer walls.

The steam from the many hot springs and the occasional giant condor made us feel as if we were dropping ever deeper into a great abyss. But as we reveled in the incredible scenery, the rapids became a bit more serious. We encountered numerous Class III and IV rapids and a few Class V’s, but we managed to eddy scout most of them and needed to make only one short portage.

Every time we scouted a rapid, Dave ran off behind a rock. He was definitely not at his best and told us that he really preferred not to paddle any Class V that day. But there was no place to camp, and we had to move onward because the walls of the canyon were becoming even steeper and the current was getting stronger.

“That looks like Reparaz!” Randy yelled, pointing to the large pyramid-shaped rock that marked the beginning of the dreaded rapid. “I didn’t think that we were that far, but that sure looks like what Duillio said.”

The sheer walls of the canyon closed in, but I managed to catch a small eddy on river left. There was a big drop right below me that I could not eddy scout, but I was able to climb onto a small boulder. Tom and Randy caught a small eddy on river right, but Dave was already too far downstream and needed to crowd into my eddy. He had been the sickest of the group in the morning, and now he was forced to share a tiny eddy on the brink of a deadly drop! He was starting to look a little green, but he managed to stay focused, finding a small handhold and waiting patiently in the eddy while I climbed on the rocks to scout.

There was a clean line, and I directed Tom, who was waiting upstream. He caught a small surging eddy next to me, and I gave him the directions for the rest of the rapid. There was one boof and a left-to-right move next to some large, undercut boulders. He got a big tail stand, and the current pushed him a little too far left, but he managed to scramble past a very large hole.

Randy followed with a clean run, and I climbed back to Dave, who was still clutching the small handhold. He was a tough old mountain man, and paddled bravely over the edge of the first drop. I watched him disappear and enjoyed a brief moment of intense solitude before following him downstream. The current was very strong, but I managed to catch a surging eddie on the left and ferried through the maelstrom of rocks and holes. A few desperate strokes finished the rapid and I was greeted at the bottom by a very joyous group.

The wonders of adrenaline had suddenly cured Dave’s stomach, so we found a sheltered spot and celebrated with a lunch of jerky and PowerBars.

We had traveled much farther than we had planned and had reached a very open section of the canyon, where the low-angled walls greatly reduced the danger of rock fall. So we decided to camp early and enjoyed a relaxing afternoon free of falling-rock anxiety.

Our only water source had been the Colca, which was very clean at the beginning but had become increasingly contaminated by sulfur from the many hot springs along the way. Mixing this with iodine for purification created a concoction that was truly disgusting, but I forced myself to choke down enough to satisfy my basic needs and settled in for an early sleep.

“Whoa! What is going on? Holy moly!”

Everyone in the group was suddenly awakened by a strange feeling that someone was kicking our tents, and the ground was shaking vigorously.

The sound of rock avalanches echoed through the canyon, and we started to realize that, not only were we in the middle of an earthquake, we were in one of the most dangerous places in the world to experience one! There was a very large rockslide just across the canyon from us, but our camp was safe, and we felt very lucky to have survived the quake.

If it had happened the night before, we probably would have all been killed, because I could only imagine what it must have been like at the Ducha del Cóndores!

None of us could sleep, so we waited anxiously for the dawn and were rewarded with a great view as the canyon came to life.

“Let’s get out of here before the ground starts to shake again,” Dave said.

He got no argument from the rest of us because there was still one more serious gorge to complete, and we were all very eager to get out of this canyon.

As we paddled, we saw numerous rock avalanches from the night before and thanked the Gods that we had not been farther upriver during the quake.

“That’s it!” Tom yelled, catching a small eddy on river right.

The Polish Canyon was a long and nasty sieve, with big boulders and a steep gradient, but there was a ledge that allowed us to portage most of it, and we could handle the rest. We needed to use our ropes to pull the boats up to the ledge, but we were still a bit dazed from the quake, and the ledge was very exposed. My knees were a bit shaky, and the rocks in the canyon seemed to vibrate as we carried our boats along the tiny ledge with the steep, rushing river below us.

The portage ended before the rapid did, but Tom found a clean line, and the rest of us followed him to the flat water at the bottom. We celebrated on a stable bank with the last of our jerky and dried fruit.

A few more miles of Class III took us back to civilization, where the local highway workers welcomed us. They stopped their work to congratulate us, and we practiced our Spanish while waiting for a minibus to Aplao. A quick phone call reassured us that our friends were safe, and we began celebrating in earnest.

This incredible gorge is still one of my best memories.

The following is a somewhat exaggerated version of the true story, used for a Toast Masters speech.

I wake up at dawn, and my senses are instantly overwhelmed by the incredible colors and the stark emptiness of the huge canyon where we have spent the night. The experience feels almost like a dream as I slowly recapture my senses and remember where we are. “Wow!” I suddenly recall what my old friend Dave Black had told me before the trip: “It’s a real scary canyon! The rapids are always changing, and there is one Class V rapid that is very hard to scout and cannot be portaged. Every run is essentially a first descent.”

The infamous Colca canyon is the deepest gorge in the world, and also contains some of the most interesting Geology on earth. I had seen an article in National Geo about a Polish Team that had explored it in the early 80’s and had been dreaming about it for more than a decade. This canyon sounded totally enchanting, and the right group of people and opportunity finally arrived.

The shuttle through the great Atacama desert of southern Peru offered a thrilling start to the expedition, and revealed how remote we would really be. The trail into the canyon used local burros and was a thrilling exchange of culture as well as a big adventure, as we dropped into the grandest crevasse on earth. The trail ended at a gentle beach, and we quickly unloaded the burros and organized our gear. The views were beyond description and became even more vivid as the daylight gradually disappeared. The black desert sky allowed a spectra of brilliant stars and we had a few hours to relax before the drama that we could not even have possibly imagined was about to begin.

The canyon was already quite deep and narrow, but the depth increased within a few moments and we felt as if were being drawn into the very depths of the planet. Some gigantic condors circled above us and their presence made the chasm feel even more supernatural. It was almost as if we had passed through time and entered a prehistoric world in the very bowels of the Earth. There were no roads, no people, and not even an airplane to distract us from the serenity of this remarkable world.

The first rapid was a constantly changing serious of class V drops but we managed to survive them and we were celebrating on a small beach when the first volcano erupted.

“Holeee Sheeet!” Exclaimed my Peruvian friend Gian Marco, as we watched the torrents of Lava and a few giant boulders spew into the river. We managed to find a reasonably safe camp and spent the afternoon watching the nearby mountain explode. The fumes from the Lava were a bit overwhelming but our camp stayed safe, and we spent a sleepless night listening to the ever threatening sounds and contemplating our fate. The night seemed to last forever, but the dawn finally came, and we carefully analyzed our choices.

The volcano seemed to be easing a bit, and the canyon walls seemed impossible to climb, so we proceeded cautiously down stream. Torrents of steaming lava were pouring down the side canyons, and the flows triggered a few rock slides that rattled our already shattered nerves. The combination of the class 5 rapids with the added challenge of dodging the flowing lava was a bit overwhelming, so we found another reasonably safe camp and hoped that the eruption would soon cease.

“That looks like a safe spot there!” exclaimed Gian Marco, as we managed to find a beach with a small cave. “We might as well drink the whisky now, because we might be dead tomorrow!” He exclaimed, as we huddled helplessly in the small shelter and guzzled our small ration of Scotch whiskey. The torrents of lava continued to flow, but the whiskey helped to ease the mental pain and we managed some restless and very needed sleep.

The rest was short, as we were rudely awakened with another sudden eruption. Boulders and lava were suddenly flying all around us, but our little cave somehow managed to survive, while the rivers of lava continued to pour into the canyon and a cloud of steam overwhelmed the view.

The action of the volcanoes suddenly eased and the scenery was absolutely stunning, but the views did not solve out dilemma, so we climbed back into our kayaks and plundered onward into the great depths.

The gradient of the river had now eased and we started to feel a bit of optimism until we arrived at the brink of a ninety foot water fall that had been formed by the recent eruption. The lava flow and rock avalanche had enclosed the box canyon, so running the falls looked like our only option. A careful scout revealed a line on the falls that did look possible, but it was a much bigger drop than either of us had ever run and it looked extremely dangerous. There was a reasonable and somewhat safe camp at the top of the falls, and we had about 3 more days worth of food, so we decided to procrastinate as long as we possibly could.

It was another sleepless night, but the dawn finally came, and the waterfall was still there to taunt us. The torrents of lava had ceased, but just as we were preparing to run the falls, the earth started to shake again. We rushed back to the sheltered spot and hugged each other while we anticipated the end of our lives.

But, just as suddenly as it had started, the trembling ceased, and we wondered back out to survey the falls. “Wow! Maybe there really is a God!” exclaimed Gian Marco, as he gave me an exuberant hug. The latest quake had broken the new dam, and the new line looked much easier. The rapid would still be challenging, but it looked doable and we eagerly climbed into our boats and paddled out of the enormous gorge.

The Best Adventure Guides in Peru