“All good things are wild and free” Henry David Thoreau

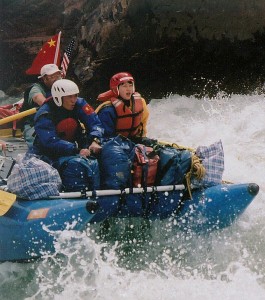

Xiao Mu (The Katie Couric of China) riding some big waves on the first descent, with Pete Winn rowing,

The sky was dark with the threat of an afternoon storm, and a strong wind intensified the eerie mood as we paddled under the last modern bridge. A throng of colorful locals — some of whom had been waiting three days for us to arrive — cheered us on from above. Our team consisted of twelve men and one woman who ranged in age from 20 to 58, spoke three different languages, and represented four different countries — China, Japan, Australia, and the United States. Most of us had not met before this trip, but we’d come together to attempt a first descent of one of the last great canyons in the world.

The Chinese government had thrown us a huge send-off party, and a diverse and curious crowd of Tibetans, including many of the legendary Khampa Warriors on motorcycles, had been watching and following us along the road for the last four days. We had just paddled through a beautiful canyon, with some big wave trains and intermittent Class III to IV rapids, and it had been great for evaluation and team building. But practice time was over — the road would soon be gone, and the rapids were getting more difficult as the river became bigger and steeper!

The political tensions between Tibet and China have historically made it extremely difficult to get a permit for the upper reaches of the Mekong River, and this was the main reason this stretch had never been run. Our group had the support of the Sichuan Scientific Expedition Association (SSEA) and included four Chinese members, which no doubt helped us get the permit. The Chinese are very proud and patriotic and did not wish to allow foreigners to usurp the glory of their first descents. The Japanese had been chosen because of their financial support and their previous expeditions on other portions of the Mekong. The other members, including myself, were old friends or friends of friends, but financial support seemed to have taken precedence over skill.

The second reason that this section had never been run was because it was very remote and probably very difficult and dangerous! It took five long days on terrible dirt roads to get there in a minibus, and scouting the canyon was virtually impossible.

I feel that the great rivers of the world are a lot like the great mountains. These special places are very sacred territory, where only the strongest of men and woman get to spend a few moments, and then only if the Gods bless them. A strong team will probably be pushed to its limit — and maybe beyond — and anything less is just begging for trouble.

In twenty years of paddling Class V rivers, I’ve had many experiences that were so incredibly good that they seemed beyond what a mortal could comprehend, and I’ve had a few experiences that were incredibly bad. Two of my best friends have died, and I have had some very close calls myself, so I have a great respect for rivers. But, I also have a very strong love for these canyons, and that is why I was there with that team. Together, we would do the best we could to stay alive and explore an untested river. I thought that I had retired from serious kayaking, but the chance at a first descent on a major river in Tibet was impossible for an old whitewater addict to turn down.

…………………………………………………………

“I see a big horizon-line drop about 200 yards ahead!” Travis shouted, as he paddled rapidly up to Pete’s raft.

We all stopped to scout and discovered a nasty ten-foot drop that had been created by a recent rockslide. The drop was short, but it was filled with sharp rocks, and even the hardcore kayakers decided to portage.

The portage was short, but it was in the middle of an active rockslide path, and dozens of large, unstable boulders balanced precariously above us. The rafts were heavy, and the terrain was hazardous, but we completed the portage in about three hours with a great show of teamwork and energy. We found a safe place to stop below the drop and enjoyed a well-earned lunch before heading on downstream.

The arduous portage left us a bit tired, so we found a camp on a sloped beach with great views next to the trail that had replaced the busy road. A few of the local Khampas stopped by to say hello and were amazed by our tents and other equipment. The canyon was becoming deeper and more pristine, and the sounds of civilization slowly disappeared. We were leaving the modern world and entering a very primitive one, where only the serenity of the canyon accompanied us and we had only ourselves to depend on. The Chinese team cooked a big feast, and we were enjoying a great evening until some very strong gusts of wind and rain sent us scurrying to our tents.

I lay in my tent listening to the storm and thinking about the team and our great adventure. The Japanese boaters were young and fearless and had incredible energy, but they had very little experience with rowing rigs; their previous expeditions had been completed with paddle rafts, which require very different techniques. But at least they understood big water and would probably be able to survive a swim.

The Chinese contingent was a mixed bag: Son Ye Pin owned a rafting company, and Fen Chun was on one of the Chinese teams that attempted the Yangtze in 1986, but the other members did not have very much experience. Liu Li was the translator and trip organizer, and Irene Mu, also a very good translator, was the star of China’s version of “The Today Show.” Communication was usually one of the biggest problems on any expedition, and having three languages more than quadrupled the problems.

The American team ranged in ability from Class IV to Class V, but most of us were past our prime. At 20, Travis Wynn was a strong, fearless probe; he had been paddling most of his life and even spoke some Chinese. His father, Pete Wynn, was 55, and he had also spent much of his life paddling or rowing. He was a veteran of many Grand Canyon trips and had boated many rivers in China. Ralph Buckley 50, was a very fit and gregarious professor from Australia who paddled very well and was a veteran of many expeditions. Steve Van Beek was still quite healthy at 58, and I was 53.

With this team, we probably would have had an exciting experience in the Grand Canyon, but this was not the Grand Canyon! We had just entered one of the last great gorges in the world that had not been run! Our maps were not very good, and it was impossible to scout from the air because this region of Tibet was essentially occupied territory, and any kind of travel by tourists was strictly regulated.

The canyon we were in was very remote, had steep walls on both sides, and had sections of twenty-five to forty-foot-per-mile drops, which could be very significant on a river this large. The volume was about 5,000 cfs where we started days earlier and had risen to about 10,000 at this camp. This was about the same as the Grand Canyon at low water, but the gradient on the Mekong was much steeper, and the rapids that we had seen changed constantly due to rockslides from the sheer walls. The rockslides could suddenly dam the river, causing huge rapids, and if there was a big slide in a box canyon, we would be in deep trouble.

In many ways, the situation reminded me of the great Colca Canyon in Peru, but the Colca had been flowing at about 1,200 cfs when I paddled it, and I had been four years younger then. Luckily, the team had very good energy, and there was a trail next to the river, so we still had an escape route. The group had enough food to last about eight more days, and we could probably buy Tsampa from one of the villages.

We awoke to a beautiful, clear morning with fresh snow on the high peaks and a light frost on our tents. The canyon walls formed a nearly perfect 90-degree angle and rose from river level to about 18,000 feet, where the snow capped summits glimmered in the bright sun.

A small, terraced village sat majestically on the right side of the river, and just below it was the biggest rapid that we had seen so far. The main current flowed next to a vertical wall, and some large breaking waves threatened to flip the rafts. A few of the rafts brushed the wall, but they all managed to stay upright, and a very happy team whooped it up at the bottom as the local villagers came out to watch.

Another afternoon storm moved in, with gusty winds and light drizzle, just as we arrived at the next big drop.

“It looks like this weather is getting worse and that rapid looks very challenging,” Pete said. “So Travis and I are going to scout downstream for rapids and camps! I don’t want to flip a raft this late in the day and get stranded.”

The rest of the group stayed upstream, and we explored a beautiful side canyon that had been carved out of a green rock called serpentine. It had been six days since we had taken a bath, and the clear, cold river felt very refreshing.

Travis and Pete returned and told us there were no camps immediately downstream, so we set up in an abandoned yak herder’s structure. We christened the camp Yak Dung Hotel and called the rapid Green Snake because of the winding riverbed and serpentine canyon walls.

The Japanese team cooked up a huge pot of chocolate curry, and we celebrated Ralph’s fiftieth birthday with some kind of rice alcohol. The skies cleared, and the brilliant stars hovered above the narrow canyon. Our GPS told us that we had gone about nine miles that day, which meant that we were already four days behind schedule just as the canyon started to get steeper and narrower.

I awoke at seven when a strong gust of wind blew my paddle against my tent. The wind was followed by torrents of hard rain, so I hid in the comfort of my modern nylon structure. At seven-thirty, I stuck my head outside and saw misting rain with ominous clouds and snow just above our camp. The expedition had started at 10,560 feet and the river wound its way through a range of nearly 18,000-foot-high mountains. A series of recent storms were clinging to the high peaks, and the bad weather drifted down into the canyon. I put on all my warm gear and headed to the kitchen, where the serious caffeine addicts had the water nearly boiling.

“Good morning campers! How is the birthday boy today?” I asked Ralph and greeted Kita.

“My head is a bit groggy, but this crisp weather is waking it up. Look at that incredible view,” he replied.

The sun was starting to stick its head out of the clouds, and the views of the river and the high peaks were truly astounding.

Everybody had a good run on Green Snake, and the jubilant group — stoked on coffee, cold water, and adrenaline — moved on downstream. The sun finally came out, but the air stayed crisp as we floated through some fun Class III wave trains. We were moving fast and having fun when Travis spotted a sharp blind turn just up ahead.

“The rafts better catch that eddy! I don’t see anymore below it!” he warned us, then paddled ahead.

The blind turn revealed two new tributaries and a long Class IV rapid with a Class V drop at the end. It would have been a very difficult and dangerous run for the rafts, so the team decided to portage.

The portage was about a quarter of a mile, which meant we had to de-rig and disassemble the rafts so that the tubes and frames could be carried separately. There was a good camp about halfway through the rapid, so we decided to portage in two sections. Our Chinese guides hired some local villagers to carry everything to the camp for the night and return in the morning to complete the portage.

“Look at that!” I said excitedly, pointing to the scar of a fresh rockslide about a mile downstream.

“It’s probably another rapid. Let’s go check it out,” Ralph suggested, and we headed down the trail to investigate.

The next rapid was easier, but also very significant. There was a clean line for the kayaks, but the breaking waves were huge, and there was an almost river-wide surging wave hole in the middle that would be very difficult for the rafts to avoid. A very large rock at the bottom could easily wrap a raft if it flipped in the big hole.

We walked back to the camp, and Ralph drew a picture of the rapid on the back of a kayak as the anxious group gathered around us.

“Do you think we can line the rafts through the worst part?” Pete asked.

“That might be a possibility,” Ralph replied. “I’ve never used that technique myself, so you’ll have to decide when you see it.”

The weather stayed clear as we settled into our new camp, and we enjoyed an incredible Sichuan dinner in another remarkable setting.

The next day started out cloudy yet warm, but the weather deteriorated quickly, and we finished the portage in a cold mist.

“There is a very good eddy above the drop on river right, so we’ll paddle down and meet you there!” Ralph told the rafters as he paddled by them. He and Travis had just run the Class V rapid, and he was grinning from ear to ear. But, as the four kayakers paddled downstream to help guide the rafts into the large eddy, the weather took a turn for the worse.

“I don’t really like any of those lines, and this weather doesn’t make it any easier!” Pete said, as we carefully scouted the rapid. “We might be able to line them down that left side, but that looks pretty sketchy, too,” he added.

“What about that right middle line?” I asked.

“That’s probably the best one, but that wave hole is really surging, and a bad surge could flip one of these rafts,” Pete agreed, tentatively.

But then he had an idea. “Let’s try one raft,” he offered, somewhat impulsively. “I’ll row it without a passenger, and the kayaks can come along for safety.”

We were very anxious to move downstream and tired of portaging, so we headed back to the eddy. Pete checked the rigging on his raft and nervously tightened the straps. He had a lifetime of experience, but this river was pushing him to his limits. He grabbed the oars, and was just about to pull out of the eddy, when a torrential downpour of rain forced him to reconsider.

“Maybe we should take a quick lunch break and see what this weather does!” he said, and everyone agreed.

There was an abandoned village next to the rapid, and some of the group had already found a dry spot.

“Crash! Boom! Bam! Crash! Splash!”

A loud noise startled us, so we looked downstream and saw a large rock avalanche crashing into the rapid — in the very spot where we had thought about lining the rafts. The avalanche also inundated one of the eddies I had thought about catching, and watching the rocks crash into the river brought back harsh memories of the Colca. The avalanche sent a very strong message to everyone else, as well, and as we hid from the rain and enjoyed a warm lunch, we all pondered how dangerous this river really was.

When the rain finally eased, it was mid-afternoon, and we decided to spend the rest of the day scouting farther downstream. The scout revealed three more big rapids in the next two miles, and I stopped to talk with Pete and Travis, who were contemplating one of the big drops.

But Pete had already made up his mind: The river was too difficult and dangerous for the rafts to continue, which meant the trip was over! I was very disappointed, but I agreed with his decision. There was a chance that the kayakers could go on alone, but we needed to discuss it with the rest of the group.

I walked downstream alone, contemplating my life and this incredible river. Even though I was definitely past my prime, I was feeling pretty good. My neck was still sore from the five-day bus ride, but the pain was fading, and my old spirit was coming back. I also knew that, between the political situation there and my age, if I didn’t make it down the canyon this trip, I would probably never come back.

My thoughts drifted to one of my favorite lyrics by Tom Waits — “Opportunity don’t knock/He has no tongue and she cannot talk” — and I tried to think rationally, while my adrenaline was pushing me to continue.

Ahead of us was about eighty miles of big-volume river in a very deep canyon, and the action was probably just beginning. The trail was disappearing, but the maps showed other villages, and the many side canyons probably had trails. I had spent enough time in the Himalayas to know that there were people almost everywhere. I also suspected that there would probably be some very hard rapids that could not be portaged, and that there might be an un-passable rapid in a box canyon. But my gut feelings and instincts told me it was a reasonable risk, and I wanted to take my chances.

I had a good supply of PowerBars and jerky that I had been saving for this moment, and I had an expedition size kayak, complete with dry bags. Travis and Ralph were not as well equipped, but the group had enough dry bags and extra equipment to suffice, so we decided that we wanted to give it a go. We had managed to convince ourselves; now all we had to do was convince the Chinese.

Suddenly, the camp erupted in a huge argument! The Japanese team was very disappointed and angry about the decision. They were young and very fit and wanted to continue with the kayakers, but the Chinese were in charge and would not let anyone go.

I could not understand most of the arguments, so I headed back to a great little cabin that I’d found under a big boulder. It must have been a seasonal home for some migrant herdsmen, and it offered a fabulous view of the mighty Mekong and the great canyon that we were about to leave.

I thought about sneaking off by myself, but I had never been much of a soloist when it came to boating. I enjoyed the company of friends, and I knew that they were indispensable in many life-threatening situations. I drifted into a deep sleep and dreamt about my close friends John and Paul, who died paddling. I always seemed to sense their spirits in these remote places, and I knew that they probably would have been busy packing their boats. I could almost hear their laughter as they taunted me, urging me to press onward.

In the morning, we had a new plan, and some of us went trekking up one of the side canyons to a truly amazing remote village. We arrived in the village at about ten and found everyone sitting in the morning sun drinking tea. We had met one of villagers during the portage, and he gave us a grand tour of his remote Shangri-La. It was the season for planting the barley, and as we left, most of the villagers headed out into their fields with their yaks.

The rest of the group was moving slowly, and we joined a huge parade of yaks, burros, and Tibetan porters, all carrying our three rafts, four kayaks, and a ton or so of miscellaneous gear out of the deep gorge.

Three days of walking took us to the busy village of Chala Shan, which resembled a trading post in the Wild West. This village sat in a pleasant valley with great views of the surrounding mountains, but the streets were littered with broken beer bottles, and I sensed a somber mood.

There was a road from there, but it was very bad, and the two 16,000-foot-high passes had not been crossed since the last storm. But, our Chinese guardians found a local truck driver who was willing to try the road, and we departed in darkness the next morning.

The dawn illuminated a spectacular setting as we bounced along the primitive road in the back of the old cattle truck. The driver stopped in a remote village to hire some of the locals to shovel the snow on the high pass, and we wound our way upward into the high alpine zone. The local villagers seemed very happy and sang a beautiful harmony.

The women were very beautiful and were decked out in jewelry that resembled Navajo work I’d seen in the States. Two hours of shoveling and pushing the truck brought us to the crest of a pristine pass, and we stopped to enjoy the view. Our food rations were waning rapidly, but we rummaged enough for a meager lunch. The Tibetans used a blowtorch to heat a large portion of meat, which was shared with all the workers.

The driver bid our snow shovelers farewell, and we started the descent on the primitive road, which was steep and very slippery. Our truck slid off of the trail on more than one occasion, and we learned how to build a path with the rocks that littered the local landscape. The task was somewhat amusing and a pleasant alternative to the portaging that we had encountered on the river. The driver tried desperately to get back on the main trail while we pushed and yelled directions in three languages that he didn’t understand. Our efforts finally succeeded, and we reached the bottom of a breathtaking and uninhabited valley, where we found a small river that needed to be crossed.

The ford looked very sketchy, but the driver gunned his engine and bounced his way through the rocky stream. Everyone was amazed by his efforts, and we enjoyed a delightful camp in a magnificent setting. The sky was clear, and the bright alpenglow illuminated the many peaks that surrounded the valley.

We awoke early, hoping that the road had frozen sufficiently to carry the weight of our truck up the last hill. The air was cold, and we were still half asleep as we tried to get comfortable in anticipation of another long ride. I heard the engine roar and felt the truck lurch forward, but our progress ceased almost immediately. The frost was not sufficient, and the truck was only able to travel about a hundred yards before it sank up to its axles in mud.

We were all very distraught, but the driver was determined, and after an hour of pushing and hauling rocks, we were moving again. The mood of the group improved greatly as we crept toward the top of the pass, but there was one more complication that could not be overcome. Our driver suddenly slid off of the road in a very precarious spot, and all of our efforts only seemed to make the situation worse. The truck was in danger of tipping over, and our situation was looking very grim when we saw two hikers coming down from the top of the pass.

The Yunnan TV crew had managed to track us down and had hired another truck, so all we had to do was transport a few thousand pounds of gear to the top of a 16,000-foot-high pass. We felt very sorry for our truck driver, but there was nothing that we could do, and we were quite sure that the many local travelers would help him when the mud dried. Carrying the gear was a good physical workout, and we raced the Japanese team members up the steep hill. The task was accomplished quite quickly, and soon, we were traveling through another pristine valley on our way to a hot spring resort in Yanjing. The resort was our intended takeout, and we enjoyed a casual afternoon in the warm water.

There was another stretch of virgin river just below us, and Pete managed to get permission for the kayakers to run it. The Mekong from Yanjing to the Yunnan border proved to be an incredible, big-water day run, with two Class V drops and some great surfing.

That part of the canyon was also the site of an ancient salt mine, and the experience was one of the best in my lifetime. We entertained the locals by surfing the glassy waves next to the ancient mine, and we all got a big thrill out of the challenging whitewater.

There was a classic, big-water class V rapid near the end of the run that had a very powerful curling wave. It was a very exhilarating drop, with fast water and a very powerful eddy line, but everyone had a successful run, and we named it Twisted Sister. It will no doubt become one of the classic rapids in Tibet if the run gets popular.

Our shuttle driver was none other than the Chinese-appointed governor of the district. He didn’t speak English, but he talked very rapidly in Chinese as he literally slid around the 90-degree turns of a narrow road that was carved into a cliff about 500 feet above the Mekong.

Our translator told us later, that he didn’t like Americans because our government was always interfering, and he was trying to scare us. He definitely succeeded — the shuttle ride had made everything else that we had experienced on the expedition seem trivial.

The shortened expedition left us with a few extra days, so we drove south through the incredible mountains of northern Yunnan and visited the famous Tiger Leaping Gorge on the Yangtze River.

I will always see the Mekong in my dreams.

……………………….

Travis Winn returned to the Mekong in March of 2008 with a strong group of young kayakers and paddled two-hundred miles of previously un-documented river all the way to Yunnan.

The group found many class V rapids, but portaged only once. This run would have been extremely difficult for the rafts.